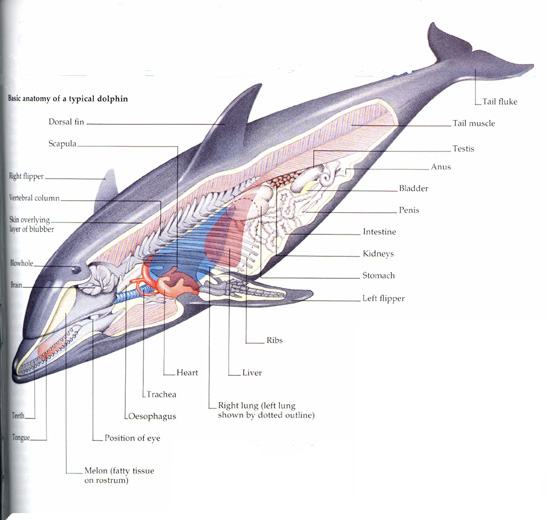

Anatomy

Skin:

The dolphin's smooth skin is constantly being sloughed off and replaced. It is sensitive to touch and easily scarred. This 'scarring' is a useful aid to researchers in helping them to identify individual animals.

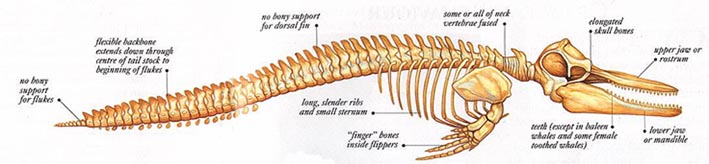

Skeleton:

The basic mammalian skeleton has undergone a number of specialized changes. The forelimbs have been modified into flippers and the bones of the hind limbs have disappeared altogether. The pelvic girdle remains as a mere vestige buried in the ventral musculature. A large number of the dolphin's ribs are 'floating'. i.e. not attached to the sternum or breastbone. Ribs that are attached are often jointed, enabling the rib cage to collapse under the pressure of a deep dive, without being damaged. The skull has become tilted upwards in line with the spinal column and the cervical (or neck) vertebrae have become fused together in almost all species.

Head:

The face of the dolphin is essentially unexpressive. Although the eyes may widen and dart about with excitement or narrow abruptly in anger, the perpetual smile of most species tells us nothing about their emotional state. Some dolphins have a well defined beak and others have none. There is no external ear, only a pinhole opening on either side of the head, which is vestigial and not used for hearing. Set in front of these, the eyes function independently of each other. The jaws are straight, elongated and narrow. Towards the back of the upper jaw, effectively the 'upper lip', is an area of fatty tissue called the 'melon'. The brain case is at the rear of the skull. The hollow lower jaw is filled with fatty tissue, known as 'panbone'. Most dolphin species have large numbers of teeth, some as many as 200. The two most notable exceptions to this are: the adult Risso's dolphin, which has no teeth in the upper jaw and no more than 14 in the lower; and the male narwhal, whose tusk is almost always its only visible tooth. Behind the melon is the 'blowhole', the external opening to the animals nasal passages. This is naturally closed and must be opened by muscular action. The two nasal passages join together into a singular tube which fits over the end of the trachea, which then passes through the oesophagus. Because the trachea and oesophagus are separate, the animal is able to feed underwater without drowning.

Kidney:

The kidneys are large and consist of many inter-connected lobes called 'renculi'. They also contain special structures which may help with filtration during diving. One might expect that dolphins would have a problem obtaining enough water to keep them alive, living as most of them do in a saline environment, and that the kidneys would have a vital role to play. In fact , Dolphins get most of the water they need from eating fish. The dolphins skin acts as an osmotic membrane, allowing water, but not salt, to enter its system. This explains why the kidneys do not appear to be very specialized.

Blood circulation:

The circulatory system of the dolphin is remarkable in several ways. One if it's extraordinary features is the presence of retia mirabilia or 'wonderful nets'. It is thought that these 'nets' of tiny blood vessels serve to protect vital organs from the effects of water pressure, and to trap any bubbles of nitrogen which may form in the blood during ascents from deep dives. Retia in the thorax and around the spine are fed with blood from arteries in the body wall and supply blood directly to the brain through arteries in the spinal canal. It is thought that this arrangement ensures a constant blood supply to the brain even during deep dives. Another specialized feature of their circulatory system is designed to conserve body heat. In the dorsal fin and the flukes, warm blood flowing towards the extremities passes through arteries which are surrounded by bundles of veins carrying the returning blood. Heat from the outgoing blood is largely absorbed by the cooler returning blood, thereby minimizing the loss of heat to the environment.

Reproductive organs:

In males, the urogenital opening is in front of, and separate from, the anus. The long retractable penis, which is normally wholly inside the body, is almost prehensile and emerges when erect. The paired testes are hidden deep within the abdominal cavity near the kidneys. Females also have a urogenital slit on the belly, within which the reproductive and excretory organs are situated. The two mammary glands are located on either side of the urogenital opening and the nipples are recessed within longitudinal slits. The shape of the baby dolphins mouth prevents it from suckling directly underwater; the mother's rich milk is therefore squirted from the nipples into the baby's mouth.

Dorsal fin:

Most dolphins have a dorsal fin, the size and shape of which varies between species. It is unclear why this structure evolved. As far as we know it has no analogue in the terrestrial ancestors of cetaceans. As the dorsal fin has no bony support, it is not surprising that it is absent from the fossil record. Some modern species (like the beluga and narwhal) lack the fin entirely and several of the river dolphins have what can best be described as a rudimentary ridge or hump-like fin. This indicates that a well developed fin on the back is not essential for cetacean survival.

Flukes:

The two flukes of the dolphin's tail are flat and horizontal, and are held rigid not by bones but by tendons and fibrous tissue. The flukes function as powerful paddles and are driven up and down by the well-muscled tail stock or 'peduncle', rather than side to side as is the case in fish. The long powerful muscles of the peduncle, some of which originate far forward on the back, need to be firmly attached to the skeleton; the dolphin's vertebrae therefore have specially adapted long spines to which they are anchored.

Basic anatomy of a dolphin